6 Challenges with matrix organizations

Burnie Group has observed the following common issues that can prevent organizations from maximizing their matrix structure’s potential:

-

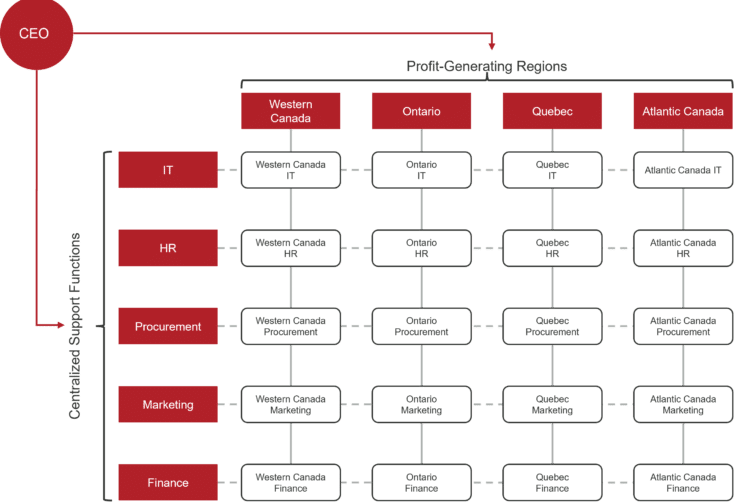

The choice between centralized and decentralized functions

When matrix organizations decentralize capabilities and resources, they emphasize specialized skills and expertise closer to an individual business unit or regional market. Conversely, centralized functions tend to be those capabilities that benefit from greater consistency in delivery and scale. Although this principle is effective in most cases, sometimes the choice isn’t obvious, and situations can occur where greater flexibility warrants more decentralized resources. Breaking these principles is usually done with good intent, but they can cause conflict amongst business leaders and lead to poor choices in the future as the organization grows.

-

Leaders having difficulty in giving up autonomy

When senior leaders believe their success was due to their dedication and hard work, it can often manifest in the personal control they feel over their teams. As a result, when these ‘Type A’ leaders are forced to share resources in a matrix structure, they can feel uncomfortable or, worse, unwilling to relinquish control to another group. When situations like this arise, two problems can occur: big issues fall through the cracks due to passive-aggressive behaviour, or duplicate effort ensues where two teams compete for the same tasks. When leaders are not naturally communicative or collaborative, intervention must occur, otherwise working in a matrix will be sub-optimal.

-

The rigidity of rules and processes

Operating models comprised of systems, rules, and processes are essential for any organization to run efficiently. However, situations can occur where exceptions may be necessary for a a specific business unit to succeed without hindering another’s operations. Nevertheless, these exceptions can also complicate operations within a matrix structure. For instance, a centralized email channel might be a logical choice for most business units that field customer queries; however, centralizing this channel universally could hinder the success of a niche business unit that conducts e-commerce transactions. In such cases, the choice to centralize could become an obstacle that impedes the business unit’s performance and negatively impacts results.

-

Unclear governance and corporate decision-making

When implemented effectively, matrices facilitate enhanced collaboration in executive-level decision-making. But when they are implemented poorly, matrices can confuse or stagnate decision-makers, particularly on decisions related to budgeting and resourcing, organizational strategy, and prioritizing ad-hoc requests. A lack of clarity results in multiple leaders believing they are responsible for an outcome, causing unnecessary escalations and lengthening the decision-making process. Alternatively, leaders may be forced to make decisions that are rushed or not fully informed.

-

Unclear roles and responsibilities

Not only can decision rights be confusing in matrix organizations, but so can responsibilities for day-to-day activities. Traditionally hierarchical organizations have the advantage of reporting to a singular leader who can make decisions about roles and responsibilities related to their business unit or function. By contrast, matrix organizations can result in individuals not knowing who owns specific tasks. Of course, when processes are documented and repeatable, it’s more apparent to all involved. Still, in our observation, this isn’t always the case. Ad hoc requests or exceptions can fall through the cracks, resulting in uncertainty about who is accountable for completing a task or activity.

-

Non-representative impact on profit and loss

When leaders own the profit and loss (P&L) of a business unit, they often want the authority to decide how to spend their budget on support functions, such as Marketing and IT. In many cases, these P&L owners are provided with an allocated cost that may (or may not) be tied to the provision of support services. This can result in inaccuracies related to the actual expenses within their unit. Although effective organizations will have controls and charge-back policies to allocate this budget, in some matrix organizations, a business unit leader is accountable for a number that does not bear reality to the actual costs incurred.

Read about how we resolved matrix challenges at a financial services organizations.

READ THE CASE STUDYResolving your matrix challenges

Although managing in a matrix can sometimes be difficult for some, the benefits can be transformative when implemented effectively. There are three common solutions to matrix challenges:

-

Establish clear guiding principles for how the matrix should function

When changing from a hierarchical structure to a matrix, an organization requires clearly defined guiding principles to inform how it will operate in practice. Guiding principles ensure a well-understood matrix across the organization and create parameters for how individuals interact.

For example, an organization can determine that strategy is established within market-facing business units, where day-to-day prioritization and decision-making can be most nimble because they are closest to their customers. To support this end, support functions with scalable capabilities can interface with these units to support the business when required. By establishing this high-level architecture for the business, general rules are established for how it operates and can inform if or when exceptions to this rule are critical to the business’ success, such as embedding support functions in the business.

Creating these parameters across the business helps people understand the matrix’s purpose, creating stronger accountability and clearer role demarcation.

-

Create a culture of communication and develop governance structures across the matrix

Communication between managers in overlapping and adjacent groups is vital to understand priorities and objectives for tasks related to shared employees. Formal communication channels with regular cadences promote the free flow of information. They can help teams to avoid duplicating work within the matrix and help leaders allocate resources to meet strategic objectives. They also empower employees to focus on their assigned tasks instead of relaying information to multiple managers.

To support this end, embedding the values of communication and collaboration into how the business will function ensures that expectations of working together to make decisions and solve problems become cultural norms. When ‘going it alone’ isn’t acceptable, people can take it upon themselves to work together and truly benefit from the matrix.

-

Apply an accountability framework to establish decision rights and ownership.

When ambiguity persists, using decision rights frameworks to help teams discuss how decisions and processes can work better can effectively resolve persistent challenges. These tried, tested and true tools, such as RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed), help individuals and teams establish where accountabilities should lie to enable organizations to operate more consistently with clarity in roles. By discussing and determining role assignments, groups and individuals within the matrix will establish where contributions are best suited and how people can support each other daily. Any conflict is resolved once, so in practice, the multitude of day-to-day challenges is dramatically reduced going forward.

That said, RACI assignments should evolve as needed. Changes in resources and strategic objectives may require assignment adjustments over time. Leaders should regularly review the organization’s RACI to incorporate changes in their landscape and address project requirements. For example, Burnie Group introduced a Consulted+ role for a client to indicate the need for additional input before making a final decision. The Consulted+ role enabled the client to align on the go-forward accountability structure, effectively improving its decision-making process and codifying team collaboration.

Although challenges can occur with any chosen organizational structure, the benefits of matrix management are plentiful. Diagnosing the specific issues is critical in establishing the best solution. Reach out to us for support with role clarity and decision rights.

About the authors

Read more of our insights on operations

Find out how our management consultants can help you unlock your organization's potential.

CONTACT US